|

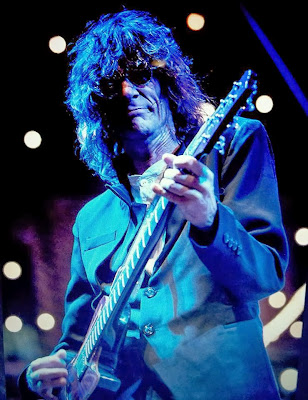

| He builds 'em, he plays 'em! |

He's not just a builder, he's also a very active player, gigging regularly in the region around his home in Pittsboro, North Carolina. He builds guitars he would like to play, in hopes that others will like them as well, a philosophy I've heard from more than one boutique instrument builder, and a logical manner in which to follow one's muse. He's also as modest and absent of affectation as one can be:

Terry McInturff: "Hey Tony, thanks for your interest in talking to me - what would you like to talk about today?"

I had earlier read one of McInturff's posts on his Facebook page, recounting an experience he'd recently had in a night club after a gig one evening that had lead to a discussion of where the guitar and the music business connected in this day and age, so I asked if he'd mind starting off by recounting that tale, and to see where it would lead our discussion:

Terry McInturff: "Sure! I had just done a show at a club down the street and this place called The Station is conveniently located on my way home, and sometimes I run into friends there, so I decided to stop by. Well, I didn't see any friends, but I saw a young man in his early twenties, speaking very knowledgeably about local bands.

"We have a thriving music scene here, thank God, in the Chapel Hill/Durham area.

"I weaseled my way into the conversation just to ask about who were some of the really interesting guitarists, young guys. He read what was the best he could come up with, but it wasn't much - I was a little taken aback, but by the same token, I'm thinking that maybe the guitar hero thing that I grew up with, it doesn't really have the same place for people any more.

"When I was a kid, I had no real interest in sports at all, my sports heroes were Hendrix, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck! That was the kind of macho that turned me on. With all due respect, I'd rather watch Jeff Beck than somebody throw a ball through a hole. That's just me talking - the band stuff seemed like a pretty good job, they got a lot of girls!

"It's different around here, industry wide too, and I read this in your article you sent me - that we're kind of hungry for the next Eddie Van Halen, or somebody like that, but I just don't know if that's going to happen. I don't know if there's an audience for it. Maybe there is, but certainly not on the level as when I was in high school - it's very different now."

I agreed, stating that while I had heard more great rock in the last couple of years than in the previous ten, it was more band and song oriented and less guitar-centric. While it may be of a different nature, rock ain't near dead:

Terry McInturff: "Bingo, man! I can relate to so many things you just said - when I mentioned that the guitar heroes are what got me going in my career, I guess I could blame them for it! But for my tastes, I had very little interest in virtuosic rock guitar guys who can play guitar like nobodies business - I think it's wonderful, but I'm much more band and song oriented, typically.

"You mentioned that there's another new wave of great rock bands coming out of England, and I'm glad to hear that! My band, The Gillettes, was one of the first punk bands out of North Carolina back in 1977-78 - that was part of the formative years for the whole rock 'n' roll community around here, and it was really exciting.

"I'm also old enough to have seen trends come and go. I remember back in the new wave days, the early to mid '80s, when there was a lot of keyboard stuff. The guitar industry really took a nosedive! Electric guitars were not selling well, particularly Les Pauls - Gibson sales were in the dumpster. Fender was still doing pretty well - it wasn't until Guns N' Roses came out, and Slash had his Les Paul. We saw within a year that Les Pauls were starting to move again. It's kind of interesting how that works."

|

| Photo by Karen Stack |

Terry McInturff: "Well, they haven't really effected me at all because I've always just built guitars that I wanted to play, things that I needed, and then hoped like hell that somebody wants the same thing!

"I build what I like, and I'm not a very trend oriented guy in terms of the guitar market, probably not to my best interests! I know guys and companies that have come and gone, certain companies have always been very adept at addressing trends, and the trend would last for three years, and then 'Whoops,' that product is now kind of obsolete, and now we need to design a new series of guitars!

"So, it really hasn't effected me that much. My client base, via my distributors and dealers, is getting older - that's the one thing that has changed."

Being a builder who does a tremendous amount of custom orders, I asked McInturff how much give and take goes on between the customer and builder when a potential client calls:

Terry McInturff: "Thanks for that question - that's an excellent one!

"If I custom build a guitar for an individual, there is a lot of communication going on. Starting with the first interview, whereupon I have to do my best to determine exactly what this person wants.

"I view this as building a sound.

"I really have to talk to this person about, 'What sound are we building?' And then in addition, there's all the cosmetic stuff, but the sound we're building is the first thing I start with. Sometimes, it's not the type of sound that I build! I do have a lot of variations in what I do, but they'll cut me mix CDs and stuff for me, and then send them to me to listen to.

"I just get as good an idea as I can of the sound of their musical imagination - I want my imagination to be as close to their's as possible. Sometimes they are not sure of what they want. They know they want one of my guitars, bless their hearts, but maybe they're not quite sure of which direction they want to go, so I'm practiced at finding out what other sounds they may already own, and we don't necessarily want to replicate those.

"I kind of give them homework sometimes. There's a way of listening to music, and I'll describe the way - let's see if that helps you determine what you would like me to make!

"Other times, my dealers will order guitars for stock in their stores, and I have a different set of parameters for those.

"But in each case, it really is building a sound. Unfortunately, that doesn't always mean picking the top board off of the stack, and then pulling another board off of another stack, and just put a basic recipe of species together. When you do that, you never know what it will sound like through the amplifier when you're done.

"I could go on and on, but all mahogany - even a different part of the same board can sound pretty damned different!"

I knew from my research that McInturff's attention to tone and resonance are second to none, so I asked him how they impact his overall build philosophy:

Terry McInturff: "My marching order as a builder is to determine the sound I am trying to build, and then to select the materials that will result in the proper sound at the end of the line, plugged into the amplifier.

"How I go about doing that may be a little different than other people, no criticism intended - what works for me works for me.

"But, even if I am building a solid body guitar, I think of it as if I am building an acoustic instrument in terms of tone. One of the things that I've learned, and this is controversial - I know I've talked and been on the forums discussing this part, and there are a lot of people who disagree with me, and that's fine, but the acoustic nature of the electric guitar, in other words, unplugged, unamplified, the nature of it sets true boundaries on what will be available to amplify. No matter what pickups you put on it.

"To explain that a little further, let's think of the acoustic sound of the guitar - let's say you grab a Telecaster off the rack and sit down, maybe even go into a bathroom where you can really hear the unplugged sound a little louder, a small reflective room. Just strum it. Play away, get to know it a little bit.

"We can think of that sound as being a ball park - there's a fence around the perimeter of the park, and all the frequencies and overtone series are contained within that ball park.

"Now - if we take pickups, different pickups, we know different pickups can create some pretty dramatic changes in our sound, but the difference between the pickups is what part of the ball park you're shining a light on, bringing forward on the soundstage. The frequencies that exist near the fence are either weakly present, especially the frequencies that are outside the fence and not present cannot be amplified by any pickups. Pickups can only sense what is within the fence.

"The acoustic nature of the Telecaster, even if you play with a lot of high gain, the resonant qualities of that chassis changes the way those strings vibrate, even if you've got a Triple Rectifier just dimed.

"It's still in play, so pickups are really important, but they can only serve what is given.

"And that's how I kind of go about it. That's my basic philosophy. Building an acoustic guitar. So, if I'm building a custom order for someone, and through our meetings on the phone, what I'm really trying to determine is the acoustic nature of what I am trying to build.

"Once I determine to the best of my ability what acoustic sound I'm trying to build, then I can proceed to sort through the wood and find pieces of wood that when they are used together will work together to eventually create this acoustic nature. Then we can start looking at choosing the microphones, i.e., the pickups.

"Let's say that someone orders a Les Paul style guitar like one of my Carolina Customs. Two humbuckers, nothing surprising there, but what is surprising is how many different shades of sound can be built off that same chassis by different selections of wood!

"I'm looking at a stack of Honduras mahogany right now - there's dozens of different tones right there, and if I put the wrong top on it and we have phase cancellations in the wrong places - what got me thinking about this was a question of yours, it kind of goes back to the mid '80s when C.F. Martin brought out their HD-28 guitar, which is a reissue of the pre-war WWII herringbone, the original D-28 dreadnaught guitar. I was a factory authorized Martin repair man, in fact, I was the only one in the city of Philadelphia, which was awesome fun!

"Anyway, when Martin brought out the HD-28s, the first couple of years, they didn't get it quite right - in other words, they were building a really high quality guitar, but they weren't shaving the braces, in a fashion as to make them voiced more along the lines of what the originals would have sounded like, so I was hired numerous times to start shaving the x-braces and some of the tone bars, as well, the braces under the soundboard are what I'm talking about.

"Through the sound-hole with a miniature plane shaving wood and tapping on the guitar - basically shifting the voice of it to the customer's desire.

"And that's when I started thinking about it, probably 1985. The acoustic nature of the guitar, and setting the parameters explains why we can go to a Guitar Center and play fifteen seemingly identical Les Paul Standards, but out of those fifteen we could easily have ten noticeable differences. Even though they have the same pickups, the same everything, but obviously the pieces of wood aren't identical, even though they are of the same species.

"I should have warned you, I can talk too much about this stuff!"

In fact, I was in guitar nerd heaven - I was soaking this in and enjoying the steeping. Terry had mentioned his stack of mahogany, so I had to ask about his wood supplies:

Terry McInturff: "This stack of Honduras mahogany I'm looking at I've owned for I guess twelve years, or so. I'm building some guitars right now that include some pieces of wood that I've only had for like six weeks, so it begs the question - what about this curing of wood I've heard about, air drying, and stuff like that?

"Well, there is a lot to be said for using tone woods that have been dried to the proper moisture content, stored properly, and allowed to sit around for ages! What happens chemically in the cell walls that comprise the wood, which of course, is a series of dead cells.

"However, it's common to see people state, 'Yeah, I'm using this wood which is a hundred years old.' Well, the funny thing is that unfortunately that piece of wood could easily be too wet to use - so, we have a very important specification that the piece of wood has to meet, and that is moisture content.

"My twelve year old mahogany, because it's been stored properly, and because genuine mahogany is the most stable wood on the planet earth. It literally is, it is reluctant to absorb moisture from the surrounding atmosphere, and so it has stayed at like 6-8% moisture content for twelve years. Other woods, such as maple absorb moisture from the atmosphere a lot faster, because it's harder than mahogany - because density and stability are not bedfellows.

"So, if I get a piece of maple in, and I electronically test it with my moisture meter to ascertain what the moisture content is, and I let it live with me in the shop for six weeks, and I monitor it for movement or warpage, cracks developing, if it's the proper moisture content and it's been proven to be a stable piece of wood then I will go ahead and build with it with great results."

Moving on to shaping the woods, I asked if there was any temptation to give up the panographic carvers, or pin routers, and go to newer CNC machinery:

Terry McInturff: "CNC machines are remarkably useful, and in fact, the one task that I do job out to a CNC shop is my fret slots.

"Because a CNC machine can cut fret slots more accurately than any of the analog methods. That usually means, there's this thing called a gang saw, for instance, that has one saw for each of the say, twenty-two frets. You slide the fretboard underneath it, and it cuts the fret slots, but the saw blades can deflect under the load, and the CNC machine is damned accurate, so I just shop that job out, just so it is dime-on.

"As far as getting a CNC machine to take over some of the duties here, I have no objections to using a CNC machine, it's just a tool. It just depends upon where in the build process it's used. Certainly, there is no mojo transferred to the wood when you drill holes in it, or route a pickup cavity, or anything like that. But really, I have no need for one - the tools that I use now, I can get plus or minus .005 of an inch on all the cuts. The quality of the cut is the same as with a CNC machine.

"The thing about a CNC machine is that you can program it, and have it running on the other side of the room. You'll have to check on it pretty often, but you can do other things, that's pretty cool!

"Unfortunately, my proprietary neck design, I've thought and thought and thought about this, and it's not possible to make it on a CNC. Because the series of steps in making a TCM neck are not compatible with CNC clamping techniques. Maybe it could be made to happen....well, I'm not sure it could. I think I'd have give up some quality there.

"That right there is a big strike against having a CNC in the shop, if I can't use it on most of the neck."

Speaking of necks, I asked Terry about his use of the 25.125" scale length, which is unique to McIntruff Guitars:

Terry McInturff: "Well, I do offer two scale lengths - the one you're asking about, I think I might be the only guy using it all these years.

"It all goes back to the first electric guitar I built starting in August of 1977, and what I wanted to do was build what has become known as a hybrid guitar - something that can surf both Fender and Gibson territory.

"Back then, Tony, it was heresy to try that because the Strat was a Strat, and a Les Paul was a Les Paul - they were two different camps, and those two guitars will never shake hands.

"Well, of course, now....

"My buddy Paul Reed Smith was thinking along the same lines as me. We both wanted to do something that would incorporate so many attributes of both. So what I did was a little simple mathematics to find what the midway point between a Strat's scale length and a Les Paul scale length, and the answer is 25.125"!

"What it's turned out to be is a scale length that either a Fender, or Gibson player can play, and shrug and say, 'Yeah, that feels great.' It has a little bit more twang and articulation than the shorter scale of the Gibson, but a little warmer and flutier sound than the longer scale Fender, so it's right in between. Paul Smith uses the 25 inch scale, which was first used by Dobro, and Dan Electro, he kind of had the same idea going on there.

"The other scale length I use is 25 5/8", which is one of several scale lengths that Gibson has always called 25 3/4", and the 25 5/8" is what you would have seen on the current version of the scale length they were using from about 1950 through the early sixties. Then they started messing around with it a little bit.

"So, it has that kind of vintage vibe about it, it really sounds great. I love the string tension on that scale, as well. Those are the two I use, that I work with right now."

Moving away from the chassis and necks, we looked towards the methods in which they are finished - McInturff Guitars are renowned for their beauty and their tones, so I asked about Terry's philosophies and methods of finishing:

Terry McInturff: "As you know, the topic of guitar finishes on tone has generated so much discussion on the internet, and once in a while I try to jump in and get my two cents in about what I've learned.

"We read a lot about the differences in sound between nitrocellulose lacquer, polyester, and the various types of urethanes, as well, and there is a lot of misinformation out there, to be honest with you.

"The finish on a guitar will effect the acoustic tonality of the chassis, and thus, it does have an effect on the amplified sound. It's not as radical as some of the other attributes of the guitar - I mean, it doesn't change the acoustic tone as much as using the wrong piece of mahogany for the neck. That wrong piece of mahogany will have a much greater effect, but it is still there, the finish effect.

"If we start going into hollow body guitars, and then most notably, acoustic guitars, we can go back to the D-28 we were talking about earlier, and the wrong finish on that is going to have a very noticeable effect.

"What we are concerned with when we're discussing the tonal role of the finish, if it's a hard finish then it's living on top of the wood, and it's not invaded, or soaked into the wood to an appreciable degree - the nitrocellulose lacquer, polyester, and the various urethanes will sound identical if the film thickness is the same between those three. So, it's the film thickness that has the effect on the acoustic nature of the chassis - not the resin that the film is comprised of. Does that make sense, do you get what I'm getting at?

"If a polyester finish is .005 of an inch thick then it will sound identical to a nitro lacquer that is the same thickness. However - it is much more difficult to get a polyester finish that thin. That's why we rarely see it, and why there is so much confusion, because polyester has a much higher solids content. You spray one coat of poly on a guitar, and it could be up to 4X thicker per coat than lacquer, so a lot of polyester finish guitars have a thicker finish, which has a dampening effect to it.

"Every finish system is a set of compromises. The builder has to decide - there's no such thing as a perfect finish, so it's choosing the best set of compromises for a particular person's needs.

"In my case, I still use old fashion nitrocellulose lacquer, because I like its set of compromises, and advantages. Now, there are lots of disadvantages to nitro, as well! Just like there are with the other finishes.

"I know this very well - I hesitate to even say how many thousands of guitars. I don't even want to think about it the numbers, it makes me want to go lie down!

"But you know, nitro as we know from perusing the forums, amongst a lot of people, nitrocellulose lacquer has this real vintage cache to it. Which, by the way, is not one of the reasons I stick with it.

"But, it does have a cache, and I go along with a lot of that, but I'm ready to draw the line and say, 'Let's not love the stuff too much - here's a list of the downsides of nitro, and there are significant disadvantages to using nitro.

"One of the disadvantages of the vintage cache, what most builders, especially the younger ones don't realize is that the lacquer we get now is not - it does not have the same working properties compared to what was available to Gibson and Martin in 1958. To closely mimic that stuff, and I have had a chance to work with and study a gallon of that stuff. It was made by a company called Nicholas, and Gibson used that company's products during a key period in their development, and a fellow actually had an unopened gallon of that stuff, still chemically active - I was able to analyze it.

"I take three different manufacturers products and I put them together in a certain ratio, and I get very close to the Nicholas formula.

"But, there's no one lacquer out of a can that's going to, you couldn't look somebody in the eye and say that the working properties of the lacquer I use is the same as that on a 1958 Les Paul - because it's not there, from any manufacturer.

"It's a little complicated, so modern nitro finishes, unless you do custom mixing like I do, and to be honest I don't know anybody else that does, except for a friend of mine who I let in on the secret. The modern nitro finishes are a lot softer than the old ones, even when they are freshly sprayed."

One step further along, and it's time to amplify what Terry has built thus far - we move on to pickups and their selection in the process:

Terry McInturff: "As I've explained, I see the pickups as microphones, but not in the literal sense.

"I use them to interpret the acoustic sound of the chassis, and the way in which that is going to create the proper amplified effect.

"Remember we were talking about shining the light onto the different parts of the ball park of overtones? That is how I go about choosing the pickups. And there's lots of other things to consider, too, like the output of the pickup.

"Sometimes someone will call me and give me a whole list of things, and what pickups they want, and I just have to kind of ease the brakes on.

"Nice and slowly, and professionally - and with courtesy, and say, 'We're getting a little ahead of ourselves, here. If we are going to build a sound then the sound is going to be built into the chassis, and then we're going to choose the microphones that will hold hands with the chassis to make it come out of the Marshall sounding the way you hear it in your head.'

"Peter Florance's Voodoo Pickups work very well for me, particularly when I am building a guitar for a dealer for stock - they are reliably the same from set to set, which I can't say about a lot of boutique winders.

"They have....how do I describe this? His PAF clones, the ones he builds for me, they'll sound good and give a few different shades of tones coming out of the chassis. They're kind of more omni-directional, if we're still talking mics, here. Some pickups are very uni-directional, if you follow me. They've got a real strong stamp, they want to build in a lot of personality, but if you put them in the wrong chassis, then it's not an organic sounding result. It can sound kind of hyped.

"The pickup industry, the whole boutique pickup replacement industry, going way back to Larry DiMarzio - was born for two reasons. For one, there were no master volumes on amps, so people wanted to push the front end of their Marshall harder, therefore, the famous DiMarzio Super Distortion was born.

"Also, it was a bit in reaction to poor quality - with all due respect, American guitars, for a lot of reasons, the '70s were not good for American guitars. The quality across the board was not that great.

"There was a tremendous demand for products, and they started cutting costs. People scratch their heads and wonder why Gibson used sandwich laminated bodies for Les Pauls, why didn't they stick to what they were doing originally with a one piece back? The reason is costing! The price of the lumber was less. Now, I've played some sandwich body Les Pauls that still had some magic - I had a '69 Les Paul Custom that was actually quite a good guitar, but it wasn't fabulous.

"So, people are complaining about the sound of these guitars, and so the pickup makers want you to think, 'You can change a set of pickups in your guitar, and you'll get the guitar you're looking for - sometimes that's true, sometimes it isn't.

"You know, Tony, I'm sure you know people who have put set after set of replacement pickups in their guitar, trying to get that guitar to sound correct, and sometimes they're just never successful. The reason they weren't successful in their quest was one of two basic reasons - either the chassis did not have the goods built into it, and no pickup can fix that, or the person really didn't have a strong idea of what they were looking for in their musical imagination.

"Another phenomenon that I'll just throw out there for you, is the risky business of using recordings as tonal references.

"That's a whole big ball of wax, there, but I'll try to keep it brief. The fact of the matter is that the recording chain - the sound comes out of the guy's amp, it goes through the whole recording chain, and the mixing and mastering process, and is eventually played through a person's stereo at home, and we have no idea what that sounds like.

"Basically, Duane Allman's Les Paul did not sound like the Live At The Fillmore album. If you were sitting in the front row, it did not sound like the record! Recordings can be somewhat useful, but I've seen pickup manufacturers market pickups that are supposed to get, say, Eric Clapton's sound on Crossroads, or Wheels of Fire. Well, that's just not true.

"You know as well as I do that when that happy moment comes when you say, 'OK, this mix is working, and we're just going to make it worse if we change anything. Let's print this mix.'

"Now, if you solo any one of the guitar tracks, it's probably not going to be a sound you'd want standing alone. Quite often, it's been carved up to serve the mix. If we listen, Led Zeppelin II was recorded with very archaic technology compared to today's standards. But even then, the layered guitars did not sound like that coming out of the amplifier. So that's a tricky bit of business, too!

"I think it's trickiest for people who are searching for a tone, but don't play in a band. If they are playing in their bedroom, and they're trying to match the sound of a record, that's probably very frustrating. If you're in a band setting you can judge your rig by how well it sits in the soundstage with the rest of the band. If you're going about it properly, i.e., serving the song and making the singer sound as fantastic as possible, then there's a lot more amps for a given person that would work than they may think."

Having covered the basics of the guitar and its making, I asked Terry to discuss the genesis and development of his flagship guitar, the Carolina Custom - the guitar is a rethink of the classic Les Paul Standard concept, and it encapsulates McInturff's philosophies very well for the purpose of discussion:

Terry McInturff: "The Carolina Custom is a guitar I resisted for twelve years.

"People would call me, and asked, 'Terry, I want you to build me a guitar with your accoutrements and such, but I want you to build me a Les Paul.' And I was saying no for years. I'd tell them to go to the Gibson Custom Shop, run the racks, and find themselves a really good Les Paul. Finally, I got tired of saying no.

"So, I had a little heart to heart with myself over a couple of cold beers one night. It was like, 'Well, Ok, maybe we should do this, but Tony, it was the first guitar I ever made that was intentionally designed to sound like another company's product. I have never done that before - never once.

"To build a guitar of my own design that was intended to sound like a vintage guitar from another company is something I had always avoided, because I thought it was something that had already been done.

"So anyway, the Carolina turned into a really fun project! Once I had decided, 'OK, I'm not going to be prideful, people are wanting me to do this, so what can I bring to the party?'

"The R&D for that guitar took many, many months of my spare time. But it was really fun, to go back to the fountain, so to speak. I was able to borrow three original '50s Les Paul Standards - one of which was excellent, and the other two were kind of, eh? OK versions, but I've played my fair share of 'Bursts and some of them are every bit as magical as we've been lead to believe. Others were obviously built in a hurry on a Friday afternoon, not at all fantastic.

"I also have reams of notes on every stringed instrument that ever crossed my bench - measurements taken and notes about the sounds - my bench notebook is one of my most valued possessions, it's also part diary. If I go back to the '80s, I'll be talking about a dot neck '59, and then right below that I'll be talking about the chick I did the wild thing with the night before. So, I'm not sure how people would take all that crazy stuff, but I went back and I looked at all the specifications, and then proceeded to go to work.

"The guitar is also heavily influenced by my Taurus Standard model which I'd been building for a number of years at that point. They share the same body shape.

"So, as usual, what I'm going to do is build a guitar I want to play, and hope other people do, too.

"That means that I need to have better upper fretboard access, and I wanted to have a larger footprint in the neck joint - in other words, a lot of glue joint surface area, because the part of the neck joint that resides prior to the neck pickup route is the most important part of the neck joint in terms of vibrational transference. So I made sure I had a lot there, and it turns out that it's a lot more than on a Les Paul.

"I also wanted a neck you could take on tour with the truss rod cover on - a real stable neck, but I'd already been doing that for years, so there were no changes there.

"The general voicing I prefer on a Les Paul is what I build into the Carolina Customs. That being defined as when we are playing on the neck pickup with a moderate amount of gain, let's say, Malcolm Young style - the opening chords of Back In Black. A real good crunchy thing, not overly saturated - fairly clean as these things go. I want to be able to play a G major barre chord at the third fret, and be able to hear the inside notes of the chord. I don't want to hear a big, woolly ball with a G major tonality. I want it to be more articulate and airy.

"So - that says a lot about how I voice the acoustic nature of my chassis. I have a ball park of acceptability. They all have their own personalities, but there is that ball park of acceptability, and they're all going to have that openness in the neck pickup region, because at the end of the signal chain we can definitely fatten things up, definitely blur things, but if we give the amp a blurry tone, we can't open up the tone without it sounding tight, you know?

"So I build the version of a Les Paul that I like, and I hope other people like it, and I'm lucky to report that quite a few people seem to like it!"

If you've stuck around this far, I congratulate you, and I hope you've learned as much as I have about not just guitar building in general, but also just how passionate and masterful this particular luthier, Terry Mcinturff is about his craft. I thought I would wrap things up by speaking about a particularly interesting instrument - the renowned Barn Guitar that McInturff built for Brad Whitford of Aerosmith, using wood from a real barn, the barn that figures so heavily in the story of the largest selling band in American history:

Terry McInturff: "Well, as it turns out, my elderly parents live only fifteen minutes away from the Barn Night Club in New Hampshire, where, as you know, is where Steven and Joe first met as teenagers, and where later Aerosmith played some of their earliest shows.

"It's hard to believe that this old barn was actually a den of evil, hahaha! It was a crazy time, and it was important to the band's history, so Brad, being one of my clients who is always interested in what I'm coming up with - I decided I'm going to go see this barn!

"Well, they let me in when I got there, and the stage is still there, the dance floor, and the bar area - there was this bench seating, and it was wide white pine with tons of graffiti, dirt, and cigarette stains, cracks, and I thought, 'Well gosh, that looks pretty interesting.'

"So, I managed to obtain some of that wood, and what I wanted to do was to keep all the dirt, graffiti, and stains on there, just as I found it. I milled the wood down from the back, protecting the show side with all that stuff on it. I milled it down really thin, approximately 3/16th of an inch thick, and then glued it on to a really resonant, rather bright piece of mahogany, and the reason I did that was because this pine had no desirable resonant characteristics at all.

"In fact, it acts as a damper of vibration - so, what I ended up doing was using wood that may have been a bit too bright for other purposes, and had this damper on it for other purposes that is going to change the predominant resonant frequency of the body! I glued it on there, and that's basically the story. I did do a chemical cleaning of that old top, just so that lacquer would stick to it, and I sprayed on very little lacquer - a very dull satin, as little as I could. And there it is!

"Tonally, it alludes to something like if you stuck a humbucker on a Les Paul Jr. It alludes to that sort of thing, but it has a lot more kerrang to it than a Les Paul Jr, even if you were to put a humbucker on it. There's a bit of a Telecaster thing living in there somewhere, as well.

"The first day he had it, within the first hour, he had it onstage and was playing Toys In The Attic on it, which is always a thrill - that's one of the great thrills of my career, seeing people using my stuff, whether they are famous, or not!

"So yeah, the concept of choosing materials to work together. I do that on all my guitars, like on the Carolina Customs - the top and back are always a matched set, so they are complimentary. I've been doing that for a long time."

No comments:

Post a Comment